The Blue River Legend of the Shawnee Princess Eva

We do not have very much information on the era of time the Shawnee Indian tribal bands occupied the southwest sections of our county. It is believed they migrated north prior to the end of 1810, so there would not have been much of a pioneer population at that time, to document any activities of the Shawnee people living here. However, one unusual tale of tragedy for a young Shawnee girl and her grieving father, Chief Four Toes, gives us a glimpse into the Shawnee band living in the Blue River Valley, near Fredericksburg. This story was handed down through several generations of Pioneer, Jacob Horner’s family and a hand written account, by his 2nd wife, of the following events is recorded in the archives of the library in the Stevens Museum.

When the first of the American settlers began arriving, in what is now Washington County, in the very early 1800’s, a band of Shawnee Indians, led by a man known to the settlers as, Chief Four Toes, lived in a village a top the hill, now referred to as; Horner’s Hill. Chief Four Toes, was likely known by this name for very obvious reasons, and just as likely, was probably a sub-chief to Shawnee Chief King Billy, who had a very large village near Paoli.

When the first of the American settlers began arriving, in what is now Washington County, in the very early 1800’s, a band of Shawnee Indians, led by a man known to the settlers as, Chief Four Toes, lived in a village a top the hill, now referred to as; Horner’s Hill. Chief Four Toes, was likely known by this name for very obvious reasons, and just as likely, was probably a sub-chief to Shawnee Chief King Billy, who had a very large village near Paoli.

Our first known contact with this group of Shawnee was through a man who came up the old Buffalo Trace from Kentucky, around 1807, recorded only by the name of; Mr. Linthicum. Mr. Linthicum wanted to homestead the land known as Horner’s Hill, and worked out a deal to purchase the land from the Shawnee, before he went and registered the property at the Government Land Office, in Jeffersonville.

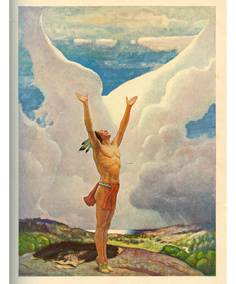

During the time the Shawnee lived in our county, horse racing had become a very popular and highly contested sport among most of the Indian tribes, and the Shawnee were fiercely competitive in the sport. At some point they constructed a racetrack, very near the present day site of Fredericksburg, and hosted regular events to test themselves and their ponies against neighboring tribes. The impression of this track was reportedly still visible into the 1950’s, when it rained a fair amount.

The enthusiasm the adults had for the sport was quickly recognized and adopted by the Shawnee youth. Both young teenaged braves and young girls took to racing their ponies through the hillsides of Washington County, at any opportunity afforded to them. Chief Four Toes children were no different. He had a daughter, Princess Eva, who adored horses and similarly relished the excitement of racing, particularly proving her merit & skills against the boys.

One day while engaged in such a race, against other youth from her father’s band of Shawnee, young Eva plunged her pony into Blue River, near the old buffalo ford. When she did, her horse crashed into a sunken tree-top that was hiding under the water’s surface, flipping itself and Princess Eva backwards into the rushing river. Little Eva’s head struck a giant rock in the water and she lost her young life that day.

One day while engaged in such a race, against other youth from her father’s band of Shawnee, young Eva plunged her pony into Blue River, near the old buffalo ford. When she did, her horse crashed into a sunken tree-top that was hiding under the water’s surface, flipping itself and Princess Eva backwards into the rushing river. Little Eva’s head struck a giant rock in the water and she lost her young life that day.

Again, we postulate, most if not all of the Shawnee population had migrated away from Washington County during the great War Chief Tecumseh’s Indian Confederacy recruitment campaign, which began in 1807 and concluded with the outbreak of the War of 1812. So we assume Chief Four Toes and his band left sometime during this time frame.

However, in 1816, the year of our statehood and roughly a year after the war had concluded, Pioneer Jacob Horner, (who would later become the 1st Postmaster of Fredericksburg), traveled up the old Buffalo Trace and paid Mr. Linthicum $25 for the lands he had previously purchased from the Shawnee Indians. Shortly thereafter, Mr. Horner erected an Inn and Tavern, to serve the weary pioneer immigrants traveling the trail into Indiana and was quite successful in this venture.

Then, according to the Horner family legend, sometime in 1817, there came a knocking at their door one late afternoon. Upon opening the door, Jacob discovered an elderly Shawnee Indian man, holding a peace pipe. Jacob invited the man inside, but he refused to enter, unless Jacob would come outside and share in smoking the peace pipe with him. Mr. Horner agreed and the 2 men found a comfortable spot under a big shade tree, to sit down, smoke and converse. The Shawnee man, introduced himself as, Chief Four-Toes and explained that this was the previous location of his village and through the years of the war, he had longed to return to his favorite hunting grounds in the Blue River Valley. The two men smoked and talked for awhile, before Jacob invited the chief inside, for dinner with his family.

During dinner, Chief Four Toes relayed to the Horner family his other reason for returning to the area. Telling them of the tragic demise of his young daughter, the Princess Eva, and his desire to honor her memory in the place she had died. Inevitably, Jacob Horner extended an invitation to Chief Four Toes to stay with his family at their Inn. The chief heartily agreed and ended up staying with them for 3 years, sharing an upstairs bedroom with Jacob’s younger brother John Horner.

During his stay, Chief Four Toes would frequently wade out to the rock in Blue River that claimed his daughter’s life. Here, he would sit atop the rock, wash his hands in the water, chant prayers and weep for young Eva. Before departing the Horner family, the chief respectively asked them to honor Eva’s memory in his absence and the family promised the aging Indian, she would not be forgotten.

John Horner took Chief Four Toes, in his wagon, to a shipping port, near the Falls of the Ohio, in 1820. Here the chief met up with many other local Indian tribes including; Delaware, Munsee, Wyandotte and other Shawnee, as they were being forced westward, by the military might of the United States Government. The chief and the other Indians took a steamer down the Ohio, towards the Mississippi and their new reservation lands, in Kansas and Oklahoma. Most departing this, “Land of the Indians”, never to return.

The Horner legend goes on to report that even after Chief Four Toes was relocated west of the Mississippi River, he continued to periodically return for extended stays, for many years. Lodging with the Horner’s, hunting with Jacob and John, and honoring the memory of his daughter with his normal rituals. When exactly the chief stopped visiting Washington County is lost to history, but the Horner family assumed the sad old man had finally passed away.

Through the years the legend of the Shawnee Princess Eva continued, as several reputable Fredericksburg citizens claimed young Eva’s spirit could still be found some nights, riding her horse along the banks of Blue River. One such story was related to the late, great, long-time historical society member, Ben Weathers, by long-time Fredericksburg resident, Laura (Beard) Martin, before her passing. According to Mrs. Martin, one morning in the early 1900’s, she was out on her porch before sunrise, on a late autumn morning, doing the chores of shaking rugs and sweeping off the porch. It was a very foggy morning, which was commonplace in the fall, living so close to the river. Suddenly, some movement along the riverbank caught Laura’s attention and through the gauzy pre-dawn light, she saw a young Indian girl, riding a pony, emerge through the misty fog. Mrs. Martin said she was frozen with bewilderment, as the young girl rode up and down the east bank of the river, as many as 3 or 4 times, before she simply dissipated into the fog.

Ben Weathers claimed he heard nearly identical stories, while growing up in that area, from later decedents of the Horner family and members of his own family, who claimed they had encounters with the spirit of Princess Eva. Ben said he camped out at least three times along those banks, hoping to catch a glimpse of Princess Eva, but was never fortunate enough to have an encounter.

Perhaps Eva’s spirit was still seeking a better crossing point in the river, or maybe she continues to ride, even today, in search of her missing people.

*This story is dedicated to the memory of 50 year Washington County Historical Society member, Ben Weathers. His efforts to preserve our county’s history, artifacts and information is sorely missed, as is his presence at the John Hay Center.